My Journey to Lifestyle Medicine

My interest in the connection between health and lifestyle began in high school as an overweight teenager with acne, allergies, and chronic nasal congestion. I noticed that certain foods relieved my nasal congestion while others made it worse. There wasn’t much information in the 60s and 70s but I read everything I could about food and disease. When I read Food is Your Best Medicine by Henry Bieler, MD, I wanted to become a nutritionist.

My interest in the connection between health and lifestyle began in high school as an overweight teenager with acne, allergies, and chronic nasal congestion. I noticed that certain foods relieved my nasal congestion while others made it worse. There wasn’t much information in the 60s and 70s but I read everything I could about food and disease. When I read Food is Your Best Medicine by Henry Bieler, MD, I wanted to become a nutritionist.

This all changed when I took my first nutrition course in college. The nutrition professor was obese, her teaching materials were mostly food industry handouts, and she made statements such as “there is no reason why newborn babies can’t eat bacon.” The four food group belief system was taught, and I tried to eat this way, but it made my acne and allergies worse. I began to experiment with different ways of eating and eliminating certain foods. When I eliminated dairy products I noticed that my allergies and nasal congestion completely resolved and they returned when I ate dairy again. Clearly there was something wrong with the belief that dairy was essential for health, because it made me sick. This got me thinking that what we are taught about nutrition is actually just cultural beliefs about food and it was making us sick instead of promoting good health.

I studied biology instead of nutrition, and became a secondary education teacher. I taught science, but occasionally I was asked to teach related subjects when there was a shortage of teachers. One semester I was asked to teach a home economics/nutrition course. This forced me to learn as much as I could about nutrition and food science to hold the interest of curious high school students and answer their questions intelligently.

In retrospect, it was divine guidance because the summer that followed I won a full scholarship to attend St. Georges University School of Medicine. The focus was the same as all medical schools, disease management with pharmaceutical drugs. There was one nutrition course which was similar to the nutrition course in college except for a few absolutely brilliant guest lecturers.

I remember one guest lecturer who discussed his research on the protective association between breastfeeding and Multiple Sclerosis. Another guest lecturer discussed studies that showed higher rates of heart disease, diabetes and cancer in populations that ate the most meat and animal fat. I was fascinated by this and read as much as I could about the connection between food and disease. I had already eliminated dairy with good results so I stopped eating meat and felt even better, but still occasionally ate chicken and fish.

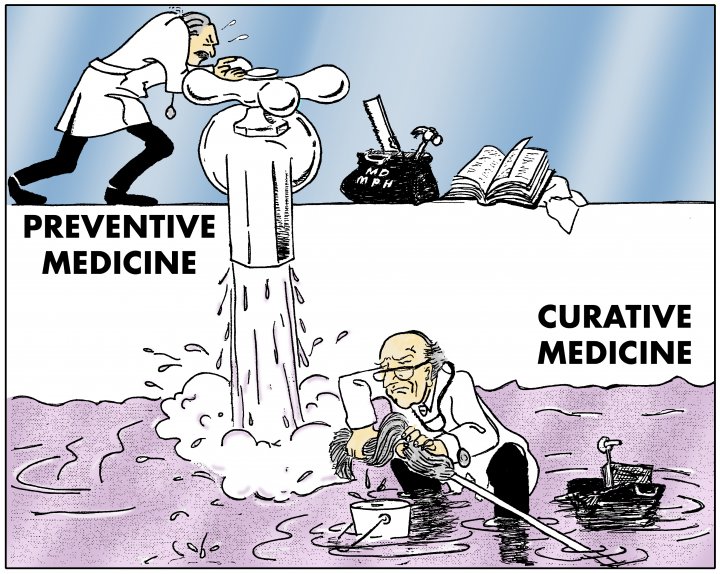

During my Internal Medicine residency, I spent long hours at Methodist Hospital caring for sick and dying patients. It always troubled to think that most of the suffering I saw could have been prevented if people simply made better food choices. In 1986, this seemed to be a radical idea, very few health professionals were making those food choices themselves, much less telling their patients to make them. I decided to switch to a Public Health/Preventive Medicine Residency Program because I thought that I could make a greater contribution to health by preventing instead of treating health problems

I loved Public Health. It is not generally appreciated, but the control of communicable diseases by preventive measures such as clean food, clean water, sanitation, hand washing and vaccines is the health success story of the 20th century. Public Health is the only medical specialty that eradicated a disease from the earth, the last case of endemic small pox was seen in Somalia in October 1977. The suffering and deaths prevented are immeasurable.

My experiences in Preventive Medicine for the control of chronic, non-communicable diseases was a different story. The focus was health program administration and screening programs to detect disease rather than on preventing diseases from occurring in the first place. I thought that would change in 1990 when Dr. Dean Ornish published the landmark Lifestyle Heart Trial which showed that heart disease, the most common cause of death worldwide, could be prevented and reversed with a plant-based diet and lifestyle changes. Nothing changed, this life-saving information has been was ignored by the general medical community and surprising also by the Public Health and Preventive Medicine community.

Inspired by the work of Nathan Pritikin, Dr. Dean Ornish and others like Joy Gross who ran health retreats where people regained their health by making lifestyle changes I stopped eating chicken and I noticed that the intermittent tarsal bursitis in my right foot completely resolved. I felt healthier and more energetic than I ever had before, but I still occasionally ate fish and seafood.

After completing my Public Health/Preventive Medicine residency, I served as the Medical Officer of Health for the Government of Grenada. I enjoyed the Public Health part of my work but was frustrated by the government’s lack of commitment to chronic disease prevention. The Chief Medical Office was obese, smoked in the Ministry of Health and abused alcohol. I could forgive one but not all three. It was tragic lost opportunity because chronic conditions such heart attacks, cancer and diabetes are most common causes of death in Grenada.

I returned to the United States, and worked with Morehouse School of Medicine, the Fulton County Health Department, and Grady Health System to integrate primary care clinical services into a Public Health clinic. It was rewarding to establish the clinic, but frustrated again by the lack of real interest in chronic disease prevention. The health care professionals had the same poor diets and health problems as the patients, the only difference was that the patients seemed more receptive to behavior change advice. It was during this period that Grady Hospital built a McDonald’s fast food restaurant in their parking deck. I don’t recall any protests from the Fulton County Health Department which is next door to Grady Hospital

I was ready for a change when I was accepted into the Occupational Medicine Residency Training Program at Emory University. I saw Occupational Health as being similar to Public Health – one promoted the primary prevention of diseases in communities, and the other promoted the primary prevention of injuries and illness in the workplace.

After residency I practiced clinical occupational medicine for nine years and became increasingly interested in the impact of a personal health on workplace injuries and illnesses. When a healthy worker with normal weight breaks a leg, he needs a pair of crutches, and the bone usually heals in a few weeks. When an obese worker with diabetes breaks a leg, he needs a wheelchair, the bone takes longer to heal, and the risk of complications from is much higher. This increases the employer’s costs, but much worse, it causes unnecessary suffering and lost wages for injured workers and their families.

During this period research on the connection between lifestyle, plant-based nutrition and and disease prevention and reversal was growing stronger and more convincing. I was inspired by the work of Dr. Caldwell Esselstyn, Dr. John McDougall and Dr. T. Colin Campbell. I completely eliminated all animal products from my diet. I felt clean, clear-headed and energetic.

In my work as an occupational medicine physician I did fitness for duty and Department of Transportation medical certification exams. Most people with chronic medical conditions such as diabetes and high blood pressure had no idea why they had these health conditions. I was surprised by the number of people who believed their high blood pressure, diabetes and other lifestyle disease was genetic and there was nothing that they could do about it except take medications. Genetics play a role, but it is a minor role compared to lifestyle. My family’s health experiences are a good example of the genetics/lifestyle balance.

My father had high blood pressure and died of thyroid cancer. My mother takes two medications to control her blood pressure and she has recently developed Alzheimer’s disease. My oldest brother had high blood pressure and died of a heart attack at age 49. My middle brother has high blood pressure and has had at least 2 heart attacks and several stents that have re-clogged. My youngest brother was grossly obese with high blood pressure and had a stroke at age 48. The stroke has left him with left-sided weakness.

I have no medical problems, and at my last doctor’s visit, my blood pressure was 110/70 with no medications. We all have the same genes; the only difference is lifestyle. I don’t eat any animal products, and I limit processed foods such as oils. When my youngest brother had his stroke in September 2009, I went to the hospital every day, and was appalled by the food that was served to stroke patients. Nineteen years after solid scientific evidence showed that arterial blockages could be reversed with a plant based diet, hospital food had not changed.

In the hospital with my brother I met a young dietitian in training who told me that plant-based nutrition was not taught in her nutrition education programs. She did a survey of her nutrition class for me, and she reported back that some of her classmates were interested, but none of them had any personal experience with plant-based nutrition. Nothing had changed since I was in college.

I walked around the hospital where my brother stayed and had the same feelings of frustration and sadness that I had as a medical resident 24 years before. Most of the suffering and pain in that hospital was was completely preventable. I decided then that I would stop complaining and follow the advice of Mahatma Gandhi to “be the change that you want to see in the world.” The timing was right. In July 2009, the American College of Preventive Medicine launched a Lifestyle Medicine Initiative which was not comprehensive, but it was good start.

In the same month, the American Dietetic Association issued a position paper stating that “appropriately planned vegetarian diets, including total vegetarian or vegan diets are healthful, nutritionally adequate and may provide health benefits in the prevention and treatment of certain diseases.” The Affordable Care Act was being launched and it promised to reform health insurance and required reimbursement for certain preventive health services.

I decided to start a practice in Lifestyle Medicine to give patients the advice that they were not getting from other doctors. It felt like divine guidance when I got an almost ideal space in Midtown Atlanta to start the practice. The clinic offered a lifestyle intervention program that included plant-based meal plans, stress management, fitness assessments, exercise prescriptions and compassionate communication skills training workshops. We had shared medical visits where patients formed community and supported each other in making healthy behavior changes.

I did not consider my clinic to be alternative or integrative medicine because I think that this is what mainstream primary care should be. Lifestyle diseases should be treated with lifestyle interventions. Doctors should advise patients on healthy ways to eat and live with and use medications only as an adjunct to get patients through the acute phases of illness while they make behavior changes that will have lasting health benefits. We trained several preventive medicine residents from Emory and Morehouse. It warms my heart to see that most of them are now practicing medicine with lifestyle interventions and their patients are benefiting and think highly of them.

In October 2012 the building that housed my office was sold and knocked down to make way for a new high rise building. We had to move, I tried but could not replicate the space or ambiance we had in our old clinic so I decided to take some time off to write a book that contained the information that we gave our patients in the clinic. Since most of our patients had high blood pressure, the first book is on high blood pressure: Stop High Blood Pressure the smart way is almost complete and will soon be published.

My brother has changed his eating habits to a strictly plant-based diet, lost over 100 pounds and is well on his way to full recovery from the stroke. He is helping me to write the book.

As a board certified occupational medicine specialist my interest now is lifestyle medicine in the workplace. Work site wellness programs would be most effective if the focus was on lifestyle interventions that actually prevented and reversed chronic health problems.